Seeds, Paintings and a Beam of Light

Similes for Dependent Arising

Bhikkhu Sunyo

Other digital formats available at Wisdom & Wonders, paper copies at Lulu.com.

I will give you a simile. For some clever people understand the meaning of something through a simile. — The Buddha[1]

Abstract

Dependent Arising is one of the Buddha’s most important and central doctrines, but in recent decades it has been interpreted in a large variety of ways. This book illustrates that the early Buddhist texts support the traditional multiple-lifetime interpretation of this teaching, taking a particular interest in the factor of consciousness. Centered around three similes, it connects this factor to rebirth and explains how it relates to the other factors of Dependent Arising. It also explains that appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa, a term used in the similes, refers to the cessation of consciousness.

Contents

Preface

About three years ago I wrote a rather technical essay on an obscure pair of Pāli words: viññāṇa anidassana.[2] These words are sometimes understood to describe a kind of consciousness of nirvāṇa, but I argued they refer to a state of meditation instead. I expected few to be interested in such technical analysis, but it was surprisingly well received. Afterwards I was asked to explain a similar pair of words that gets likewise misunderstood, namely appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa. Initially I was reluctant to do more of the same, but then realized it would be a good opportunity to illustrate some aspects of the Buddha’s teachings which continue to amaze me and which may also amaze the reader, because this subject is a good example of how interconnected his teachings are, of how words and concepts reappear throughout the discourses, illuminating the same ideas from different angles. It also gives me a chance to showcase the Buddha’s beautiful use of metaphors for even the deepest of concepts, hopefully shedding some light on the more enigmatic parts of his teachings on Dependent Arising.

As such, this writing is not meant to be a critique but a constructive step towards a better understanding and appreciation of the Buddha’s teachings. But for context, let me briefly lay out the views I consider to be mistaken. The assumption is that enlightened beings experience a certain kind of objectless or contentless consciousness which the Buddha called appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa, usually translated by proponents of the idea as ‘unestablished consciousness’.[3] Some further think this consciousness lies outside of conditioned phenomena and will continue to exist after the enlightened being passes away. Often referenced in support of these ideas is a passage wherein the Buddha supposedly compares this unestablished consciousness to a beam of light that does not land on any surface.[4]

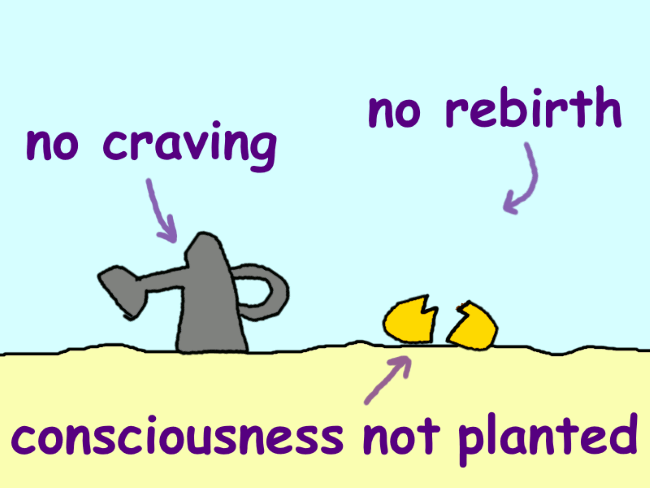

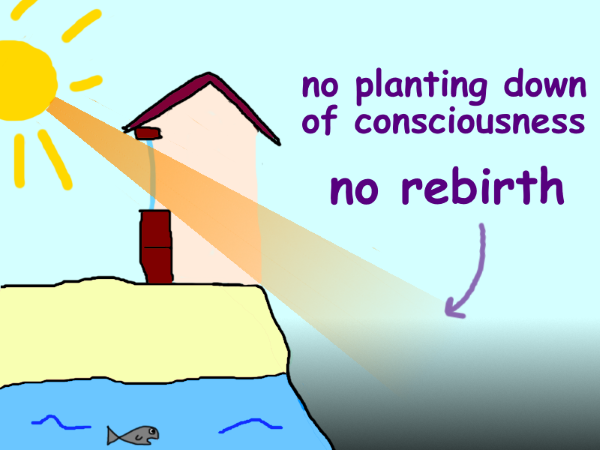

With this book I wish not to be argumentative but aim to present an alternative interpretation of the terms and simile in question. At some occasions, however, I do address the idea of an objectless consciousness directly. This was inevitable, because in my understanding the Buddha specifically denied the existence of such a consciousness, and this happens to be the exact point he was making with appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa. I will show that the term refers not to an unestablished consciousness but to the non-establishing of consciousness in any object or place, particularly at the enlightened being’s time of death, after which there will be no rebirth and hence no more consciousness. Also involved is a simile in which consciousness is a seed for rebirth, where appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa is more aptly translated as ‘consciousness is not planted’.

All this is explained in three parts:

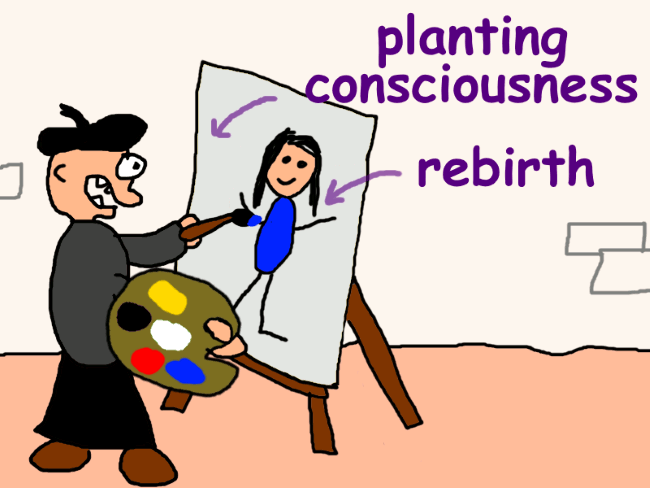

- The first part introduces the wider context of Dependent Arising and a simile of painting a picture of a person, which illustrates the creation of rebirth. It also provides some historical context for the factor of nāmarūpa, quite literally ‘name and form’, translated here as ‘the (individual’s) immaterial aspects and body’.

- The second part explains the simile of the seed of consciousness, clarifying that this simile, like that of the painting, illustrates rebirth too. It also discusses the dependent existence of all consciousness, the impossibility for consciousness to be without object or content.

- The third part gives my interpretation of the disputed simile of the light beam, showing that this simile implies the cessation of consciousness. Some connected statements on the final goal are also touched upon.

Since this writing is essentially a patchwork of translations and notes made over the span of nearly a decade, there will be a few tangents along the way as well. My hope is that these will not distract from the main ideas but add to them instead. Some of these tangents may also reflect that I am not an academic but a practitioner interested in the real-life application of these texts and that I write with a similar audience in mind. Still, please know that this is first and foremost a study of texts, not a guide to practice. A proper understanding of the texts can guide the practitioner in the right direction, however. If anything, I hope you will find some inspiration in the Buddha’s rich metaphors.

Unless otherwise indicated, quotations of the Buddhist canonical texts should be attributed to the Buddha. All translations of the Pāli, including any inevitable shortcomings in them, are my own. Unfamiliar translations will always raise some questions, but to not interrupt the continuity of ideas, I will not explain every translation choice I made and include the Pāli terms only when deemed relevant. Some translations directly connected to the topic are explained in the endnotes, which further contain only references to the source texts and contemporary works.

Realizing that the Pāli Canon is not infallible, I also consulted the Chinese Āgamas, assisted by English translations of others. My knowledge of these texts is limited, so I cannot claim this to be a proper comparative study of early texts—nor was it intended to be—but some interesting observations were made regardless. I hope this will encourage a wider recognition of the Chinese canon and less reliance on unique Pāli passages.

My highest wish, and the real purpose behind this book, is for the Buddha’s words to help the reader find the escape from suffering. I will share some further thoughts on this in the conclusion.

With gratitude towards my teachers and supporters, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Sunyo

Bodhinyana Monastery, Australia

January 2023

Part I. The Simile of the Painting

1. The aggregate of consciousness

The all-encompassing scope of the aggregates

A handful of suttas in the Pāli Canon contain appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa, the term which I intend to show does not refer to an unestablished consciousness of nirvāṇa (nibbāna in Pāli) but to the cessation of consciousness. The If There is Desire Discourse (§23) will be our main focus, because it contains the disputed simile of the light beam that does not hit anything.

But first an important point on the five aggregates: form, sensation, perception, will, and consciousness (rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṇkhāra, viññāna). Most readers will be familiar with them, but many may not know why the Buddha called them ‘aggregates’ (khandhas). The suttas say they are so called because they include, or they “aggregate”, all the different types of the item in question.[5] A khandha is literally a heap or a collection. The aggregate of perception, for example, is the collection of all perceptions. The same principle applies to the aggregate of consciousness (viññāṇa):

§1. The aggregate of consciousness includes any type of consciousness whatsoever—whether past, present, or future; here or elsewhere; internal or external; coarse or subtle; lowly or sublime. That is how the term ‘aggregate’ applies to the aggregates.[6]

That this statement is intended to be all-encompassing is clarified even further elsewhere when the Buddha says: “any type of consciousness whatsoever—whether past, present, or future [and so on]—all consciousness …”[7]

Similar phrases are spoken of the other four aggregates, so if we were to suppose some special type of consciousness that’s excluded from the aggregate of consciousness,[8] we also open the door for similar types of form, sensation, perception, and will. We then have to admit that the definitions of the other aggregates are also not all-encompassing. But this is not the intent behind these statements, which the Buddha meant to be comprehensive. As said, all types of consciousness are included in the aggregates, just like all types of form, sensation, perception, and will.

Accordingly, throughout the entire corpus the Buddha never tells his audience there is a consciousness outside of the aggregates. In one discourse a god called Baka seems to claim there is such a consciousness, but the Buddha disagrees with him.[9] Whenever he uses the word ‘consciousness’, it always refers either to the whole aggregate of consciousness or otherwise to a certain part of it. This is the whole purpose of his definition of the aggregate: to make sure we don’t leave any type of consciousness out.

Consciousness in the If There is Desire Discourse

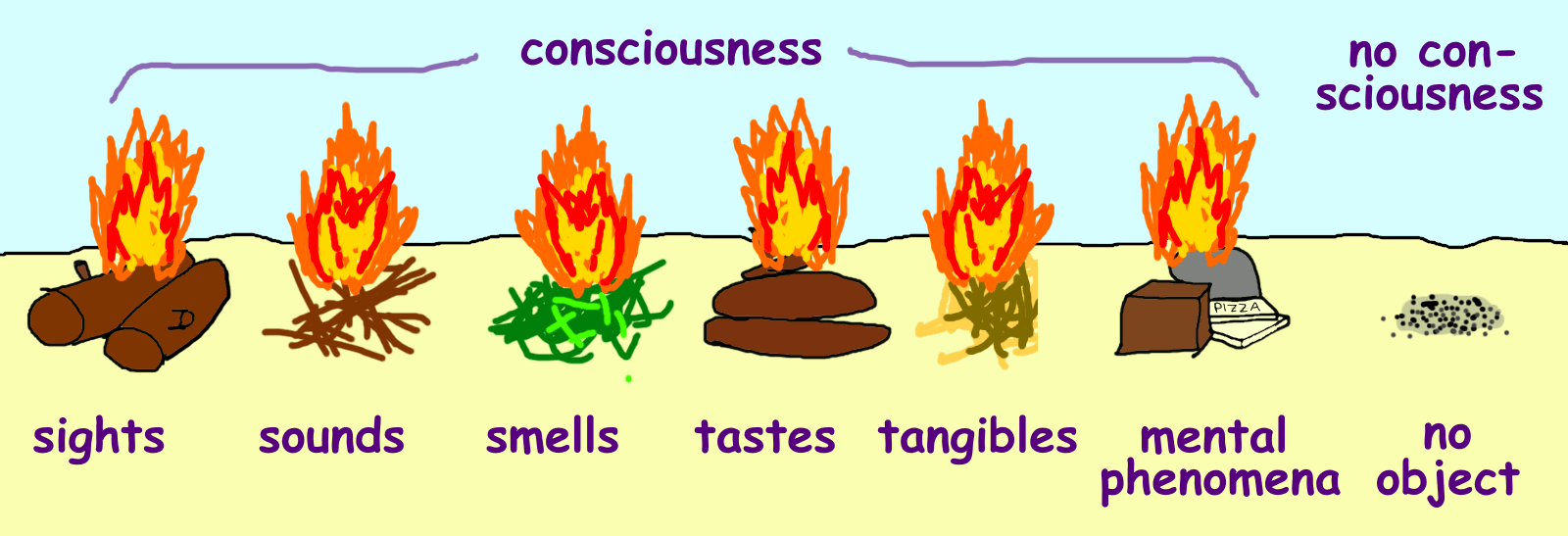

That ‘consciousness’ refers to the aggregate is even more clearly the case for the If There is Desire Discourse. It is located in the Nidāna Saṃyutta, the connected discourses on Dependent Arising, and in this context ‘consciousness’ is repeatedly and explicitly defined as the consciousnesses of the six senses—which is to say, as the aggregate of consciousness:[10]

§2. And what is consciousness? There are six kinds of consciousness: sight-consciousness, hearing-consciousness, smell-consciousness, taste-consciousness, touch-consciousness, and mind-consciousness. That [taken together] is what’s called consciousness.[11]

Throughout the If There is Desire Discourse, including the simile of the light beam and appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa, ‘consciousness’ refers to this aggregate. We are not dealing with a special type of consciousness that is outside of this aggregate (or outside of this ‘aspect of existence’, as I will translate khandha from here on).

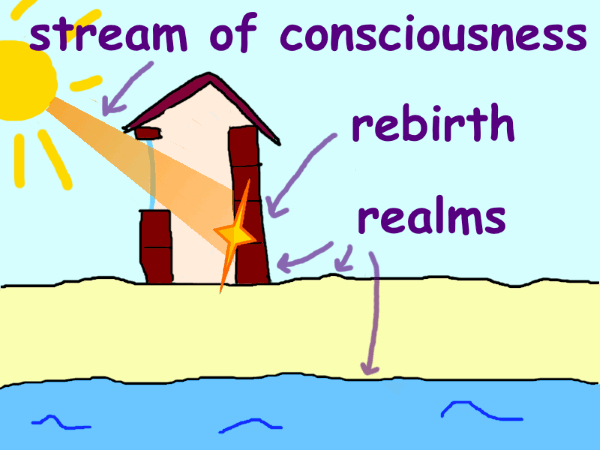

Moreover, the discourse contains not just the simile of the light beam which is sometimes taken to describe a type of “unestablished” consciousness of nibbāna. It is preceded by a simile of a painting which describes an establishing of consciousness. With this information the well-informed reader may already be able to tell what is going on, once they recall that the discourse is on Dependent Arising. In brief, the simile of the painting illustrates the origination sequence of Dependent Arising; the simile of the light beam illustrates the cessation sequence. The former sequence includes the arising of consciousness; the latter includes its ceasing. So appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa is actually about the cessation of consciousness.

All this will be explained in detail in this book. But before we consider the If There is Desire Discourse and its similes, we need a general understanding of Dependent Arising first.

2. An overview of Dependent Arising

The origin of suffering

In my opinion the best way to explain Dependent Arising—also called Dependent Origination—is by starting with the second noble truth (or ‘noble one’s truth’, as I translate ariyasacca).[12] This truth tells us that the cause of suffering is the craving that leads to a next life:

§3. And what is the noble one’s truth of the origin of suffering? It is the craving that leads to a next life, which, along with enjoyment and desire, looks for happiness in various realms.[13] That is what’s called the noble one’s truth of the origin of suffering.[14]

Dependent Arising is in essence an expanded explanation of this truth:[15]

§4. And what is the noble one’s truth of the origin of suffering? Dependent on ignorance, there are willful actions. Dependent on willful actions, [the continuation of] consciousness. Dependent on consciousness, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. Dependent on the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, the six senses. Dependent on the six senses, sense impressions. Dependent on sense impressions, sensations. Dependent on sensations, craving. Dependent on craving, fuel/taking up. Dependent on fuel/taking up, [further] existence. Dependent on existence, birth. And dependent on birth, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress come to be. That is how this whole mass of suffering originates. That is what’s called the noble one’s truth of the origin of suffering.[16]

Dependent Arising is often believed to be a very complicated teaching, but it is not. It’s very deep, very hard to see, but it should not be theoretically difficult. As said, it is essentially an explanation of the second truth of the noble one, and explanations should not be much more complicated than the thing they try to explain!

Venerable Sāriputta once explained the fundamental principles of Dependent Arising quite succinctly:

§5. The Buddha said: “If you see the dependent arising of things,[17] you see the Dhamma [the truth/teaching]. If you see the Dhamma, you see the dependent arising of things.” And what has dependently arisen are these five taken up aspects of existence. Wanting them and holding on to them, being attracted and attached to them, will make suffering originate. Removing and abandoning the want and desire for them, will make suffering cease.[18]

The arising of the five aspects of existence here means their overall existence. By this I mean, Sāriputta is talking about the origination of these aspects of existence as a whole, not about momentary changes within them. This origination of the aspects of existence happens at the start of life, when one is born. This is reflected by the definition of ‘birth’ in §20, which includes “the manifestation of the aspects of existence”. Sāriputta’s summary of Dependent Arising therefore aligns with the noble one’s second truth, on the craving that leads to a next life. That is to say, Dependent Arising primarily explains why rebirth happens.

Another short version of Dependent Arising likewise mentions that the origination of the five aspects of existence happens through birth, which in turn is caused by enjoyment and attachment:

§6. And what is the origin of form, sensation, perception, will, and consciousness? Then you enjoy, welcome, and keep holding on. You enjoy, welcome, and keep holding on to what?

You enjoy, welcome, and keep holding on to form. It results in enjoyment, and when there is enjoyment of form, there is fuel/taking up. Dependent on fuel/taking up, there is [further] existence. Dependent on existence, there is birth. And dependent on birth, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress come to be. That is how this whole mass of suffering originates. [Similar for the other aspects of existence.][19]

Because the aspects of existence are suffering which starts (or, more accurately, restarts) at birth, the Buddha also said:

§7. Mendicants, the arising, continuation, production, and manifestation of form is the arising of suffering, the continuation of diseases, and the manifestation of old age and death. The arising, continuation, production, and manifestation of sensation, perception, will, and consciousness is the arising of suffering, the continuation of diseases, and the manifestation of old age and death.

The cessation, subsiding, and disappearance of form is the cessation of suffering, the subsiding of diseases, and the disappearance of old age and death. The cessation, subsiding, and disappearance of sensation, perception, will, and consciousness is the cessation of suffering, the subsiding of diseases, and the disappearance of old age and death.[20]

The arising, continuation, production, and manifestation of the aspects of existence here means their continuation into a new life after death. It is this kind of continuation which results in more deaths: their continuation while one is already alive does not. Accordingly, the words ‘production’ and ‘manifestation’ are also found in the very definition of birth, namely in the phrases ‘the production of beings’ and ‘the manifestation of the aspects of existence’. In fact, the word for ‘production’ (abhinibbatti) also means ‘rebirth’.[21] Venerable Sujato translated it as such in the above discourse, and Venerable Bodhi did so elsewhere.[22]

The aspects of existence, and therefore death and other suffering, cease only when the enlightened being passes away. As the Buddha said after the death of the enlightened monk Dabba:

When Sāriputta mentioned the cessation of suffering in §5, he referred to this final cessation of the aspects of existence. It is only then, after one final death, that old age and death and all suffering are truly overcome.

It is important to realize that Dependent Arising explains rebirth and its causes. If we fail to acknowledge this, it becomes impossible to properly understand the Buddha’s similes and terminology, including appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa. But since some prevalent interpretations don’t recognize or otherwise marginalize this central principle, I will return to it throughout this writing, showing in various ways that Dependent Arising indeed focuses on rebirth. My apologies if at some point this becomes repetitious, but I think a topic as important as this deserves to be treated thoroughly.

The principle of dependency

Although Sāriputta’s explanation in §5 captures the most important principles of Dependent Arising, it is still a summary. Dependent Arising is usually explained with a sequence of twelve factors starting with ignorance and ending with old age and death and all other suffering. These factors are:

| Pāli | Translated here as | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Avijjā | Ignorance |

| 2 | Saṅkhārā | Willful actions |

| 3 | Viññāṇa | Consciousness |

| 4 | Nāmarūpa | (Individual’s) immaterial aspects & body |

| 5 | Saḷāyatana | The six senses |

| 6 | Phassa | Sense impression |

| 7 | Vedanā | Sensation |

| 8 | Taṇhā | Craving |

| 9 | Upādāna | Fuel/taking up* |

| 10 | Bhava | Existence |

| 11 | Jāti | Birth |

| 12 | Jarāmaraṇa | Old age & death |

(* Upādāna means both ‘fuel’ and ‘taking up’, and often both meanings are implied. No single English word conveys both, so unless only one applies, I use the dual translation ‘fuel/taking up’. The idea is that craving acts as the fuel for the continuation of existence after death, but also that a next existence is taken up due to craving.)[24]

The sequential arising of these twelve factors is usually followed by their sequential cessation, which has no official name in the discourses. Some have termed it ‘Dependent Cessation’, but I will just call it ‘the cessation sequence’. In the following text the Buddha gives both the arising sequence and cessation sequence in their standard form, after, just like Sāriputta, saying he is concerned with the arising and cessation of the five aspects of existence.

§9. Mendicants, I, the Truthfinder—with ten powers and four reasons to be self-confident[25]—claim the place of the alpha bull, roar my lion’s roar in gatherings, and put in motion the Supreme Wheel, saying: ‘This is how form is, this is how it originates, and this is how it disappears. This is how sensation is, this is how it originates, and this is how it disappears. This is how perception is, this is how it originates, and this is how it disappears. This is how will is, this is how it originates, and this is how it disappears. This is how consciousness is, this is how it originates, and this is how it disappears.

There will be this, only if there is that. This arises, because that arises. If there isn’t that, there won’t be this. If that ceases, this will cease. That is to say:

Dependent on ignorance, there are willful actions. Dependent on willful actions, consciousness. Dependent on consciousness, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. Dependent on the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, the six senses. Dependent on the six senses, sense impressions. Dependent on sense impressions, sensations. Dependent on sensations, craving. Dependent on craving, fuel/taking up. Dependent on fuel/taking up, existence. Dependent on existence, birth. And dependent on birth, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress come to be. That is how this whole mass of suffering originates.

But if ignorance completely fades away and ceases, willful actions will cease. If willful actions cease, consciousness will cease. If consciousness ceases, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body will cease. If the individual’s immaterial aspects and body cease, the six senses will cease. If the six senses cease, sense impressions will cease. If sense impressions cease, sensations will cease. If sensations cease, craving will cease. If craving ceases, fuel/taking up will cease. If fuel/taking up ceases, existence will cease. If existence ceases, birth will cease. And if birth ceases, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress, will cease. That is how this whole mass of suffering ceases.’[26]

The Buddha first says he will explain how the five aspects of existence originate and cease, which means he is concerned with how life is brought about and how it comes to a complete end. He will base his investigation on a principle which he words as follows:

- There will be this, only if there is that.[27] This arises, because that arises.

- If there isn’t that, there won’t be this. If that ceases, this will cease.

- In other words, this depends on that.

We can rephrase this more modernly as:

- There will be B, only if there is A. B arises, because A arises.

- If there is no A, there won’t be B. If A ceases, B will cease.

- B depends on A.

Much has been philosophized about these short sentences, but the principle they describe is not difficult to understand. For the sake of illustration, here is first an example of the principle applied to something outside of Dependent Arising:

- There will be rain, only if there are clouds. Rain happens because clouds form.

- If there are no clouds, there won’t be rain. If the clouds disappear, the rain will stop.

- Rain depends on clouds.

The point is simple: there can be no rain without clouds. In other words, rain requires clouds. Clouds are needed for rain. Rain depends on clouds. Or, for those familiar with logical terminology, clouds are a necessary condition for rain.

But the Buddha did not apply his investigation to rain, nor to any other phenomena in the outside world.[28] He was interested in suffering, which is found inside of beings. So next is an example of the principle that stays within the context where it was meant to be applied, that of Dependent Arising:

- There will be death, only if there is birth. Death happens because birth happened first.

- If there is no birth, there won’t be death. If birth ceases, death will cease.

- Death depends on birth.

Put simply: you will die because you were born; but if you don’t get reborn, you won’t die again.

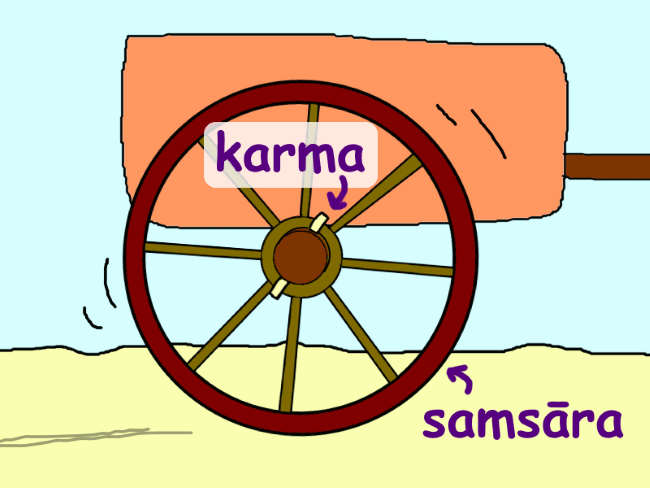

This principle is called ‘dependency’ (idap-paccayatā),[29] which explains the name ‘Dependent Arising’ (paṭicca-samuppāda). The words paccaya and paṭicca both come from the verb pacceti, meaning ‘to fall back on, to depend on’. The principle has also been called ‘conditionality’, which loses the link between these two terms but means the same.

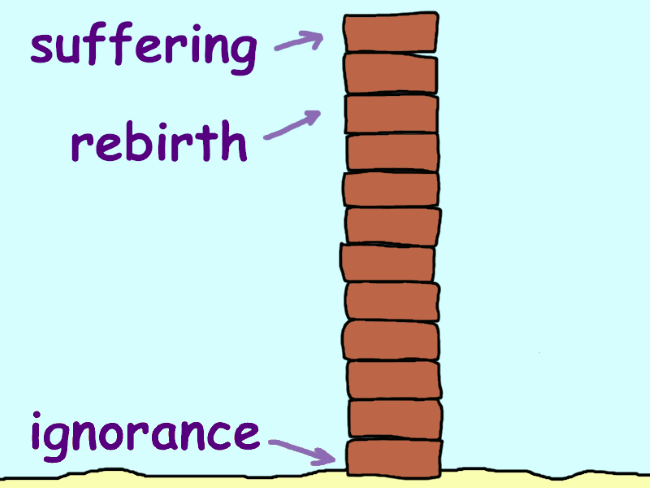

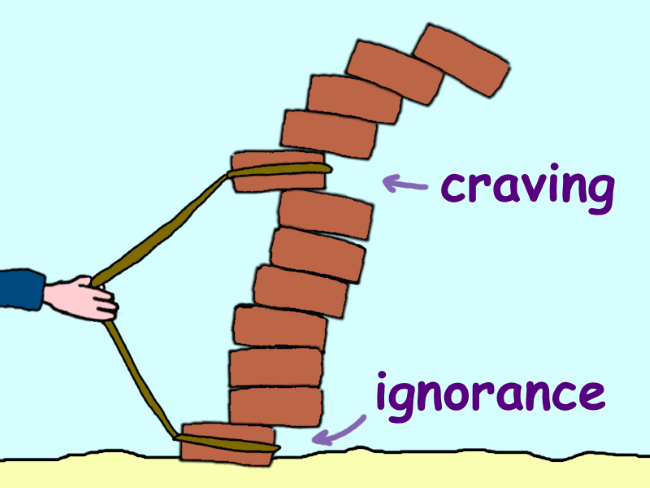

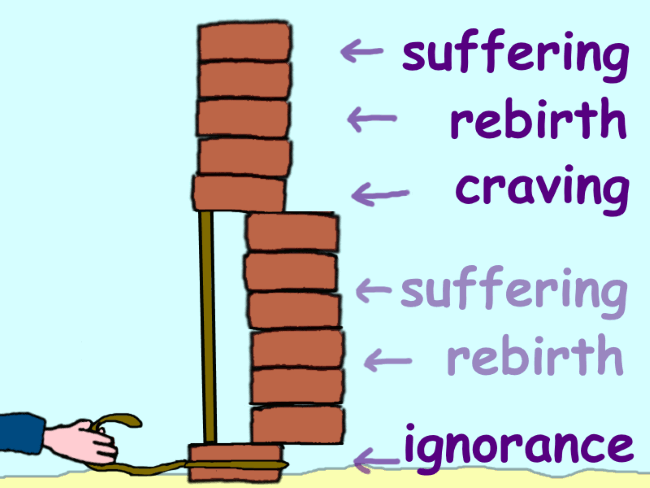

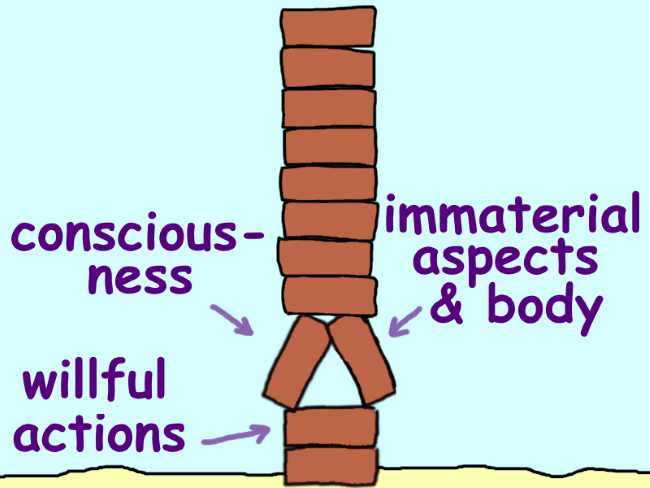

The principle of dependency applies not only to birth and death, but to all the links: death depends on birth, birth depends on the continuation of existence, and so on through the rest of the chain. So in the end all factors rely on ignorance. Imagine a tower of twelve bricks stacked on top of one another. If you remove the bottom brick, the whole stack will come crashing down. Why? Because the bricks supported one another, and they all relied on the bottom brick. Similarly, if you remove ignorance, all the other factors also will cease to be. Why? Because in the end they all depended on ignorance. If you end ignorance, you will therefore also end suffering. It takes some time for the tower to fall down, though. Suffering does not end immediately when ignorance ends, but only at the end of life.

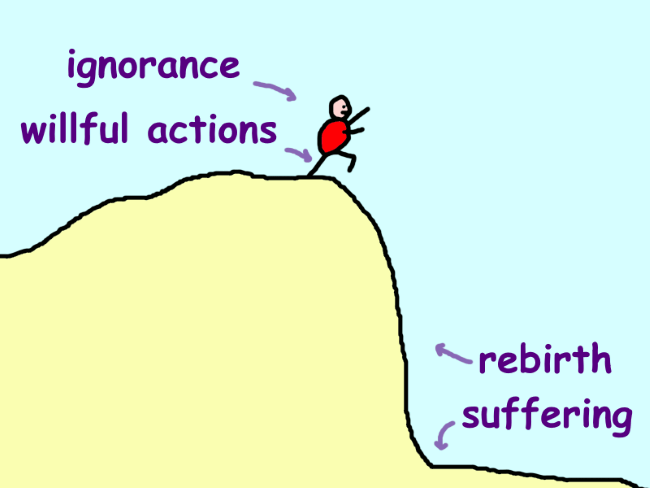

To illustrate:

Since this may all sound rather theoretical so far, I must emphasize that the principle of dependency is a means of reflection, not a mere philosophical theory. Whenever it is mentioned in the Pāli Canon, it always describes someone’s empirical insights or reflections. For example, in §49: “You closely and properly focus on the dependent arising of things, reflecting: ‘There will be this, only if there is that. […] That is to say: Dependent on ignorance […]” The principle is meant to be applied to your personal experience to understand, among other things, how you yourself have been creating rebirth and may do so again in the future.

The centrality of rebirth

Many of the links in Dependent Arising are not only necessary conditions but also sufficient conditions.[30] Sufficient conditions guarantee their outcome. For example, if there is birth, there will always be death as a consequence. Birth guarantees death. Therefore, birth is a sufficient condition for death (as well as a necessary one). But not all links are sufficient conditions. Just like a cloudy sky does not guarantee that it will rain, sensations don’t guarantee craving, for example. If they did, there would be no way to stop craving! So sensations are not a sufficient condition for craving. Likewise, craving and ignorance do not guarantee birth, because you may have those defilements today, but get enlightened tomorrow, whereafter you will not be reborn again. So your craving and ignorance were not sufficient conditions for birth. That said, this distinction between necessary and sufficient conditions can quickly become too technical, if it hasn’t already. It is not mentioned in the discourses either, so it may be better to not overthink it. The links that are sufficient conditions are quite clear anyway, once the meaning of the factors is explained.

However, there is one link where sufficiency may not be evident, and it just so happens to be the most important one: that between birth and suffering. It means that once you are born and alive, suffering is inevitable. Only by not getting reborn again, can you end suffering. This insight forms one of the backbones of Dependent Arising. Rebirth therefore is the primary issue this teaching addresses. As the Buddha said to Ānanda:

§10. It is because of not understanding and not penetrating this teaching [of Dependent Arising] that this population […] does not leave behind the plane of misery, the bad destinations, the nether world, and transmigration (saṃsāra).[31]

The focal point of Dependent Arising is also very clear in the next passage. Here the Buddha says he obtained his own insights into Dependent Arising after wondering how rebirth can be stopped. He investigated this matter using the principle of dependency in its various phrasings, starting at old age and death and working his way back to ignorance. Discourses like this are usually abbreviated, but to clarify how the principle of dependency applies to all links, I included it in full.

§11. Mendicants, before my awakening—when I was heading for awakening but not yet fully awake—I thought: “Oh no! People have really gotten into trouble. They are born, age, die, pass on, and are reborn again. Yet they don’t see any escape from this suffering, this old age and death and so on. When will an escape from all this finally be found?”

Then I thought: “There will be old age and death, only if there is what? What do old age and death depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be old age and death, only if there is birth. Old age and death depend on birth.

Then I thought: “There will be birth, only if there is what? What does birth depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be birth, only if there is [further] existence. Birth depends on existence.

Then I thought: “There will be existence, only if there is what? What does existence depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be existence, only if there is fuel/taking up. Existence depends on fuel/taking up.

Then I thought: “There will be fuel/taking up, only if there is what? What does fuel/taking up depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be fuel/taking up, only if there is craving. Fuel/taking up depends on craving.

Then I thought: “There will be craving, only if there is what? What does craving depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be craving, only if there are sensations. Craving depends on sensations.

Then I thought: “There will be sensations, only if there is what? What do sensations depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be sensations, only if there are sense impressions. Sensations depend on sense impressions.

Then I thought: “There will be sense impressions, only if there is what? What do sense impressions depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be sense impressions, only if there are the six senses. Sense impressions depend on the six senses.

Then I thought: “There will be the six senses, only if there is what? What do the six senses depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be the six senses, only if there are the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. The six senses depend on the individual’s immaterial aspects and body.

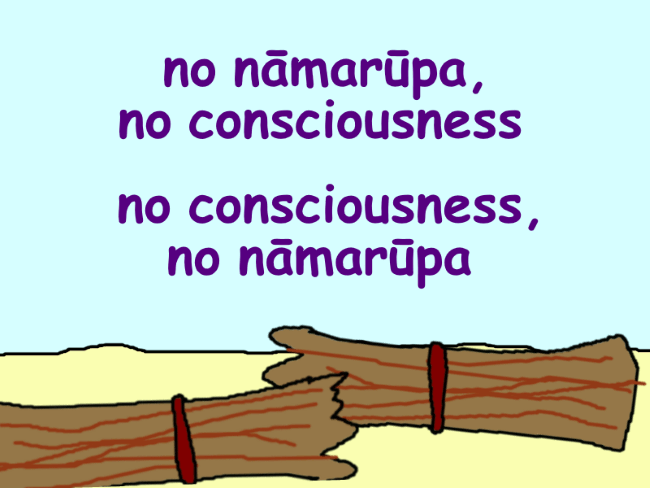

Then I thought: “There will be the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, only if there is what? What do the individual’s immaterial aspects and body depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, only if there is consciousness. The individual’s immaterial aspects and body depend on consciousness.

Then I thought: “There will be consciousness, only if there is what? What does consciousness depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be consciousness, only if there are willful actions. Consciousness depends on willful actions.

Then I thought: “There will be willful actions, only if there is what? What do willful actions depend on?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there will be willful actions, only if there is ignorance. Willful actions depend on ignorance.

So, dependent on ignorance, there are willful actions. Dependent on willful actions, consciousness. Dependent on consciousness, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. Dependent on the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, the six senses. Dependent on the six senses, sense impressions. Dependent on sense impressions, sensations. Dependent on sensations, craving. Dependent on craving, fuel/taking up. Dependent on fuel/taking up, existence. Dependent on existence, birth. And dependent on birth, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress come to be. That is how this whole mass of suffering originates.

Mendicants, that is how I understood origination, gaining insight, comprehension, understanding, knowledge, and illumination of things not taught before.

Then I thought: “There won’t be old age and death, if there isn’t what? Old age and death will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be old age and death, if there is no birth. If birth ceases, old age and death will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be birth, if there isn’t what? Birth will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be birth, if there is no existence. If existence ceases, birth will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be existence, if there isn’t what? Existence will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be existence, if there is no fuel/taking up. If fuel/taking up ceases, existence will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be fuel/taking up, if there isn’t what? Fuel/taking up will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be fuel/taking up, if there is no craving. If craving ceases, fuel/taking up will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be craving, if there isn’t what? Craving will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be craving, if there are no sensations. If sensations cease, craving will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be sensations, if there isn’t what? Sensations will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be sensations, if there are no sense impressions. If sense impressions cease, sensations will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be sense impressions, if there isn’t what? Sense impressions will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be sense impressions, if there are no six senses. If the six senses cease, sense impressions will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be the six senses, if there isn’t what? The six senses will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be the six senses, if there are no immaterial aspects and body. If the individual’s immaterial aspects and body cease, the six senses will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, if there isn’t what? The individual’s immaterial aspects and body will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, if there is no consciousness. If consciousness ceases, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be consciousness, if there isn’t what? Consciousness will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be consciousness, if there are no willful actions. If willful actions cease, consciousness will cease.

Then I thought: “There won’t be willful actions, if there isn’t what? Willful actions will cease, if what ceases?” Then, by focusing properly, I comprehended it, understanding that there won’t be willful actions, if there is no ignorance. If ignorance ceases, willful actions will cease.

So, if ignorance completely fades away and ceases, willful actions will cease. If willful actions cease, consciousness will cease. If consciousness ceases, the individual’s immaterial aspects and body will cease. If the individual’s immaterial aspects and body cease, the six senses will cease. If the six senses cease, sense impressions will cease. If sense impressions cease, sensations will cease. If sensations cease, craving will cease. If craving ceases, fuel/taking up will cease. If fuel/taking up ceases, existence will cease. If existence ceases, birth will cease. And if birth ceases, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress, will cease. That is how this whole mass of suffering ceases.

Mendicants, that is how I understood cessation, gaining insight, comprehension, understanding, knowledge, and illumination of things not taught before.[32]

In this text ‘old age and death’ is used as a shorthand for all suffering. This is a common feature in the discourses, especially those on Dependent Arising. Old age and death are a shorthand for suffering not only because they are some of its more noticeable forms, but also because as long as there still is a possibility for old age and death—that is to say, as long as you are alive—there will still be suffering. To clarify, in the Discourse on Direct Conditions it is suffering which is said to be directly dependent on birth, not old age and death as in the standard sequence. It says: “And what is the direct condition for suffering? Birth, you should answer.”[33] This also reinforces what was mentioned before, that once a being is born, suffering is inevitable as long as they are alive.

The meaning of the factors

While the principle of dependency and its application to the twelve factors are conveyed very clearly in the previous discourse, the actual meaning of the factors is not. The Buddha did not explain what ‘birth’ exactly refers to, for example. Most suttas on Dependent Arising similarly mention the standard sequence with little to no explanation of what the individual factors mean. I can think of two main reasons for this, and they are important to consider if we want to properly understand Dependent Arising.

One, the bare twelvefold sequence is not meant to be a full explanation itself, but primarily serves as a mnemonic device (something easy to remember).[34] The audience would have heard more detailed explanations and definitions of the twelve factors in other discourses, which they would have had in the backs of their minds while listening to the more bare sequences of factors. We should do the same, not taking the factors in isolation but consider how they are used and defined elsewhere. If we were to focus on the twelve words and ignore the wider context, we could give these words—which moreover are in an ancient language that is not completely understood—almost any meaning we’d like.

Two, to people back then the individual links would have been more self-explanatory than they are to us. Many of the links may make immediate sense to us as well, such as that between birth and death and that between sensations and craving. But some links do not make sense right away, like that between consciousness and the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, especially when the latter (nāmarūpa) is translated as ‘name and form’. The Buddha discovered a timeless principle, but the words he used to explain this principle are not timeless. They were spoken at a specific point in time, to a certain audience that had different ideas than us. This we should also take into account. If we interpret these historical texts too much from a contemporary perspective, we are bound to misunderstand things. In linguistic studies this is called presentism: “the anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past”.[35]

The language gap and cultural divide also mean someone could fully understand the general principle of Dependent Arising through direct insight, even be fully enlightened, but still not understand what words like nāmarūpa mean (or what any Pāli word means, for that matter). For this reason we should also be careful to stay objective about the texts and not interpret them too much in light of our own subjective ideas, even if we are very wise. If we do have deep insights, it does become a lot easier to interpret the words rightly, but it is still no guarantee. Unfortunately, insight into the Dhamma does not come with miraculous linguistic abilities!

The reader should also be aware that translations are by their nature always imperfect. As K.R. Norman, one of the greatest Pāli linguists, said: “It is very difficult to give a one for one translation of Sanskrit and Pāli words into English. It is very rare that one Sanskrit or Pāli word has exactly the same connotations, no less and no more, as one English word.”[36] This is even more true when dealing with topics as abstract as Dependent Arising. But leaving words in Pāli is no solution either, as Norman also continued to say, so I use English terms here, accepting their inevitable shortcomings. The meaning of these terms will have to be clarified by their explanations more so than by the translations themselves. This applies especially to ‘consciousness’, as we shall see.

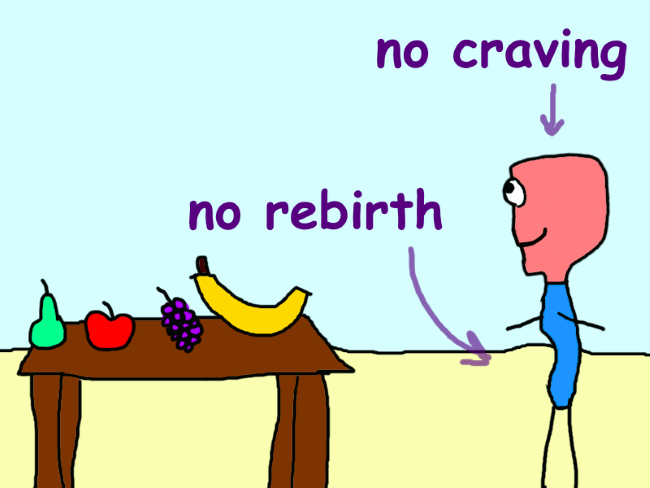

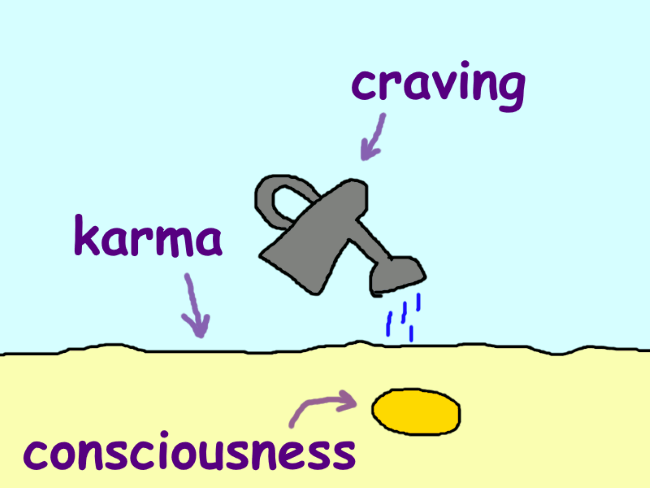

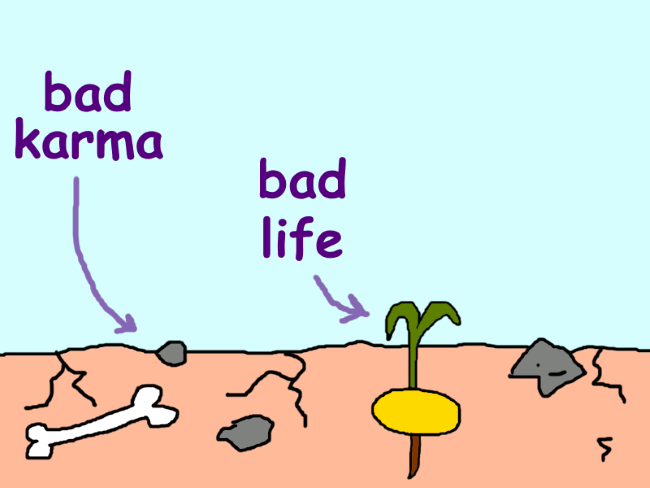

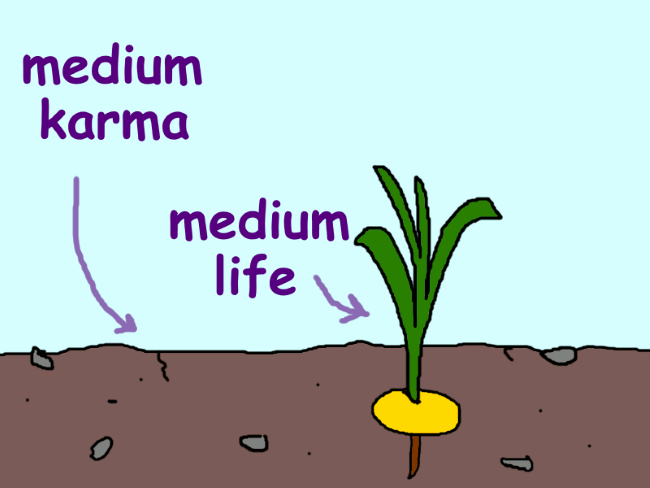

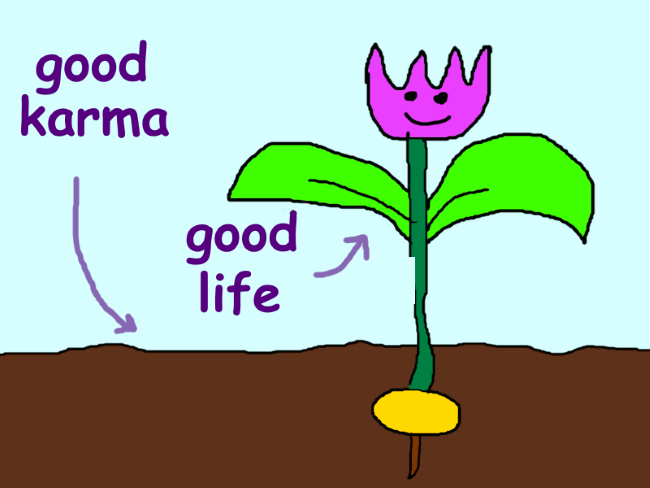

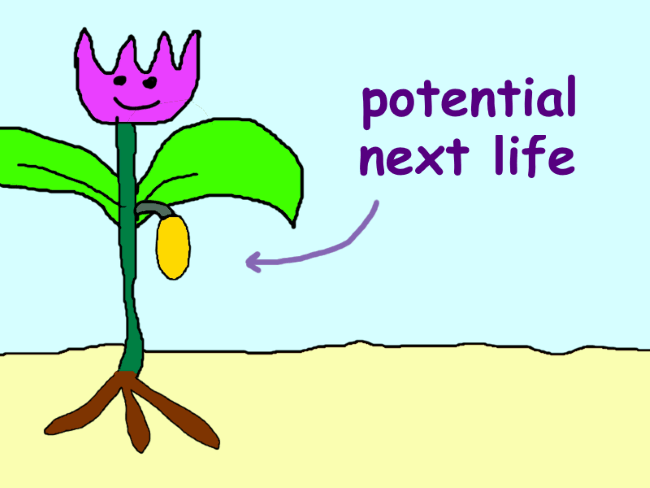

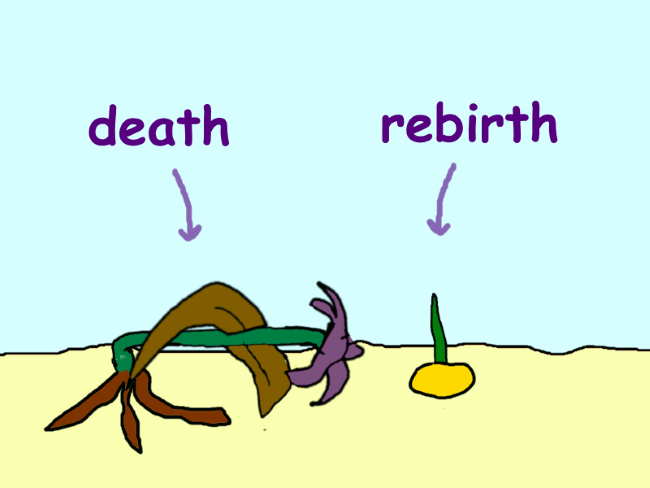

Summary of Dependent Arising

With the above principles in mind, I arrived at an understanding of Dependent Arising that differs little from that of most traditional Buddhist schools.[37] All will be explained in detail later, but to give a general overview: Unenlightened beings don’t know the true nature of life, not understanding suffering and its causes. Deluded by this absence of knowledge, or ignorance, they perform certain intentional acts, also known as karma. At death, driven along by craving, these willful actions direct the being’s consciousness into a next life—in part through guilt and rejoicing over past actions, in part through acts of the will arising around the time of death itself. The being’s actions influence where they take rebirth and thereby also shape the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, with the ‘immaterial aspects’ being general features of the being’s “inner world”. When beings are born, there are the six senses, the five physical ones plus the mind. When these senses are aware of things, there are sense impressions, which result in pleasant, painful, and neutral sensations. As long as there still is ignorance, craving arises to experience certain sensations and avoid others. Such cravings will continue at the time of death, when it becomes the fuel for rebirth. Or, from a different perspective, out of craving beings take up the five aspects of existence again. This fuel/taking up causes a next existence after death and a resultant birth in a next life. Once the being is born, there is suffering, including old age and death. But when the being gets enlightened, ignorance and craving disappear, and the whole chain collapses. Then suffering will come to an end at death, when all experiences cease as the six senses disappear.

All this can happen because there is no solid essence in any part of existence, no self involved in any of the links. This absence of a self (anatta) is not explicitly mentioned in the standard sequences, but it is always implied. It is explained in many discourses on Dependent Arising, and is of utmost importance for a correct understanding of it. However, it is not the focus here, so I will discuss it only in passing, primarily in Chapter 12 to explain why the cessation of existence (including consciousness) is not the annihilation of an essence.

To better illustrate the functions of the twelve factors, the table below displays them alongside the standard truth on the origin of suffering, the craving that leads to a next life. (‘Next life’ translates puna-bhava, more literally ‘re-existence’.) Since words are fluid but tables are not, this overview may box in some of the factors a bit too strictly. For example, the factor of existence is not just part of the rebirth process, it also continues after birth. The same applies to consciousness and the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. But the table can serve as a useful general overview, as will similar tables that are to follow.

| Ignorance sequence | Craving sequence | Second truth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of rebirth |

1. Ignorance 2. Willful actions |

8. Craving 9. Fuel/taking up |

• Craving |

| Rebirth | 3. Consciousness 4. Imm. aspects & body |

10. Existence 11. Birth |

• A next life (‘re-existence’) |

| Results of rebirth |

5. Six senses 6. Sense impressions 7. Sensations |

12. Suffering, incl. old age and death |

• Suffering |

The sequence from craving down to suffering I call the ‘craving sequence’ and all preceding factors the ‘ignorance sequence’. These two sequences function side by side in the creation of a next life. Both contain factors pertaining to rebirth, which means the twelvefold sequence describes the process of rebirth twice, illustrating the same process from two different angles. This is useful, because it lets us reflect upon the origin and cessation of suffering in multiple ways. The Visuddhimagga says the two are different ways of teaching which are suitable for different people.[38] To generalize, we might say the ignorance sequence focuses on the ethical and cognitive aspects, the craving sequence on the emotional and existential ones.

The double inclusion of the process of birth in the full sequence fits the Buddha’s inquiry in §11: “They are born, age, die, pass on, and are reborn again.” It also emphasizes that every birth is a rebirth. It is often assumed that in the Buddha’s India everybody believed in rebirth, but the discourses regularly mention the materialistic view of a single lifetime. This could have prompted the Buddha to describe the process of birth twice in the sequence, clarifying that it is about rebirth.

Possible development of the twelvefold sequence

Later chapters will repeatedly show that there are indeed two parallel descriptions of rebirth in the twelvefold sequence, but the link between sensations and craving already hints that at this place two shorter sequences may have been joined together. Take the statement, “if sensations cease, craving will cease”. While this may theoretically be true, the actual way to end craving is not through ending sensations. Craving can only be ended through wisdom, through removing ignorance. The link between sensations and craving therefore seems a little artificial, possibly inserted to connect the two shorter sequences into the twelvefold one.

Based on various other grounds, many scholars have come to similar conclusions.[39] Tilmann Vetter for example concluded: “Two different chains of dependent origination of suffering were superficially combined into the twelvefold chain. The first part (links 1–7) [the ignorance sequence] is a more developed attempt at explaining the origin of suffering than the second part.”[40] Franz Bernhard likewise thought: “It is noticeable that factors 8–12 [the craving sequence] are just a further elaboration of the basic idea of the four noble truths. […] Originally the Buddha identified only thirst [i.e. craving] as the cause of rebirth […] later—apparently influenced by and in controversy with competing contemporary systems—came then the rationale for rebirth through avidyā, ignorance.”[41]

Text-critical evidence for such a possible development comes from three Chinese parallels to the Mahānidāna Sutta.[42] They all start with the craving sequence beginning at old age and death, later mention a sequence going from craving down to consciousness, but never combine the two into the longer ninefold sequence found in the Pāli version, which goes straight from old age and death down to consciousness. See the table below, where for sake of comprehensiveness I also added the Dīrgha Āgama parallel to the same sutta, which contains all twelve factors.[43]

| MĀ 97, T 14 & T 52 (two shorter sequences) | DN 15, Mahānidāna (9-fold sequence) | DĀ 13 (full 12-fold sequence) |

|---|---|---|

| • Old age & death • Birth • Existence • Fuel/taking up • Craving ————————— • Craving • Sensations • Sense impressions • (Six senses, T 52 only) • Imm. aspects & body • Consciousness |

• Old age & death • Birth • Existence • Fuel/taking up • Craving • Sensations • Sense impressions • Imm. aspects & body • Consciousness |

• Old age & death • Birth • Existence • Fuel/taking up • Craving • Sensations • Sense impressions • Six senses • Imm. aspects & body • Consciousness • Willful actions • Ignorance |

As another indication for the combination of the two parallel sequences, one Pāli discourse joins the craving sequence in its cessation mode to part of the ignorance sequence in its origination mode. In this discourse the cessation of craving does not depend on the cessation of feeling, as in the default sequence.

§12. And what is the cessation of suffering? A sight-consciousness arises dependent on the sense of sight and sights. The combination of the three is a sense impression. Dependent on sense impressions, there are sensations. Dependent on sensations, there is craving. But if craving completely fades away and ceases, fuel/taking up will cease. If fuel/taking up ceases, existence will cease. If existence ceases, birth will cease. And if birth ceases, old age and death, and sorrow, grief, pain, sadness, and distress, will cease. That is how this whole mass of suffering ceases. That is the cessation of suffering. [Similar for the other five senses.][44]

Discourses such as this may have been precursors to the standard twelvefold sequence. I do not wish to discuss the possible development of this sequence further here, however, as such analysis quickly becomes overly speculative. My point is simply that it is one piece of evidence for seeing two parallel descriptions of rebirth in the twelvefold sequence. And to clarify, unlike some scholars I do not mean to suggest the twelvefold sequence, or any other version of Dependent Arising in the Pāli Canon, was devised by someone other than the Buddha.[45]

Ignorance and craving as the two roots

When the twelve factors of Dependent Arising are seen to contain two parallel sequences, craving and ignorance together become the primary causes for rebirth. A Tibetan commentary to the Udānavarga indeed separates the twelvefold chain into two shorter parallel ones that start with these two factors.[46] The Visuddhimagga also states: “When speaking of the cycle of rebirth, the Blessed One made two things the starting point: ignorance […] and craving for existence.”[47]

Two sequential discourses in the Itivuttaka neatly illustrate the last point.[48] These discourses are included below, but first it will be helpful to know that transmigration (saṃsāra) in the canon always means the cycle of repeated birth and death, never some sort of mental wandering, and that delusion (moha) is a close synonym for ignorance,[49] as also borne out by these verses:

§13. Those who journey again and again,

transmigrating through births and deaths,

going from one state of existence to another:

their destinations are just due to ignorance.Ignorance is indeed the great delusion

because of which we have long transmigrated.

But beings who have attained knowledge

do not go on to a next life.[50]

The two discourses from the Itivuttaka on ignorance and craving:

§14. I heard this was said by the Buddha, said by the enlightened one: “Mendicants, I don’t see any other obstruction, obstructed by which people continue to roam around and transmigrate, like the obstruction of ignorance. Obstructed by ignorance, people continue to roam around and transmigrate for a long time.”

That is what the Buddha said, and this is said about it:

“There is no single other thing

obstructed by which people

continually transmigrate

like being blinded by delusion.Those who abandoned delusion,

who pierced the mass of darkness,

transmigrate no more,

since they lack the condition for it.”I heard that this was also said by the Buddha.[51]

§15. I heard this was said by the Buddha, said by the enlightened one: “Mendicants, I don’t see any other chain, chained by which people continue to roam around and transmigrate, like the chain of craving. Chained by craving, people continue to roam around and transmigrate for a long time.”

That is what the Buddha said, and this is said about it:

“A person who has craving as a spouse,[52]

transmigrates for a long time,

going from one state of existence to another,

never getting out of transmigration.Craving is the origin of suffering.

Once mendicants know this problem,

they should wander without forgetting it,

free from craving, not taking anything.”I heard that this was also said by the Buddha.[53]

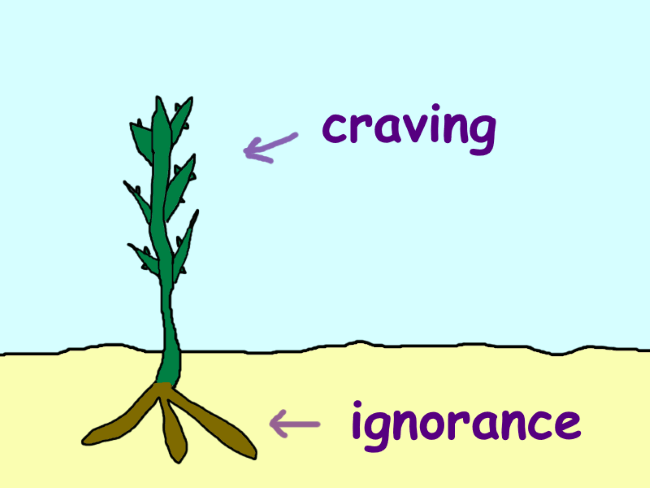

The close connection between ignorance and craving also presents itself in the phrase ‘obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving’ (or ‘hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving’). This phrase occurs frequently, always in direct connection with rebirth, most commonly in, “the transmigration of beings who roam around obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving”.[54] Other examples are: “Existence in a future life is produced because beings, obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving, look for happiness in various realms” and “the fool’s current body originated because they were obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving [in the past life]”.[55] Particularly relevant for our discussion on consciousness is a statement in §71: “The consciousness of beings who are obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving, gets planted in the lower [or middle or higher] realm. That is how existence in a future life is produced.”

Ignorance and craving are also found as a pair in other contexts. In the Sangīti Sutta they are even recited as a specific group of two.[56] Their joint connection with rebirth also comes to the fore in verses such as the following, where craving is sometimes substituted by desire (rāga):

(A charnel ground is a place where corpses are deposited without burying them.)

§17. Men set out for certain death,

always being close to the King of Mortality.

And when they discard this body here,

they go where they desire.Obstructed by ignorance,

knotted by the four knots,[58]

caught in the net of the tendencies,

the body drowns in the flood.Hidden by delusion,

chained by the five obstructions,

afflicted by thoughts,

following craving, the root.That is how the body occurs,

driven by the mechanism of deeds.

Its acquirement ends in perishing:

falling apart, it perishes.Blind fools, ordinary people,

who think the body is theirs,

taking next lives,

swell the horrible charnel grounds.Those who avoid this body

like a dung-smeared snake,

having expelled the root of existence,

the undefiled, will get fully extinguished.[59]

(The five obstructions (nīvaraṇa) are the five hindrances in meditation.)

In the last passage, which is spoken by Kappa, craving is called the root for birth and death, which it is also called elsewhere.[60] As we shall see shortly, ignorance is sometimes also called the root. To my knowledge, none of the other twelve factors is ever called such, which again shows that ignorance and craving were regarded as the two most fundamental causes of rebirth.

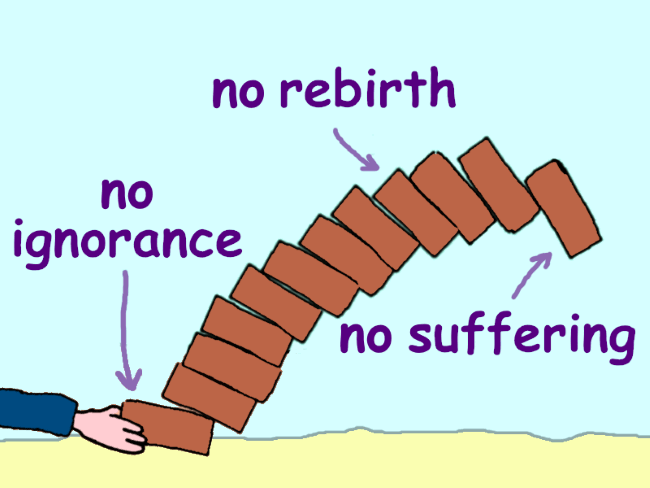

To return to the tower of bricks, since ignorance and craving are intrinsically connected, when you pull out the brick of ignorance, you pull out craving at the same time. See the following drawing:

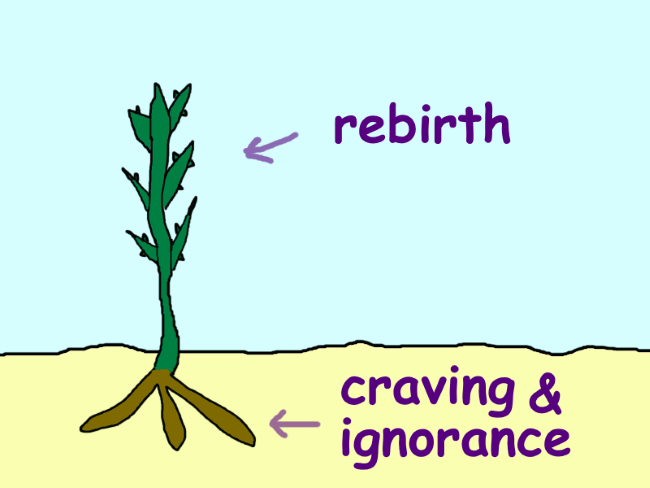

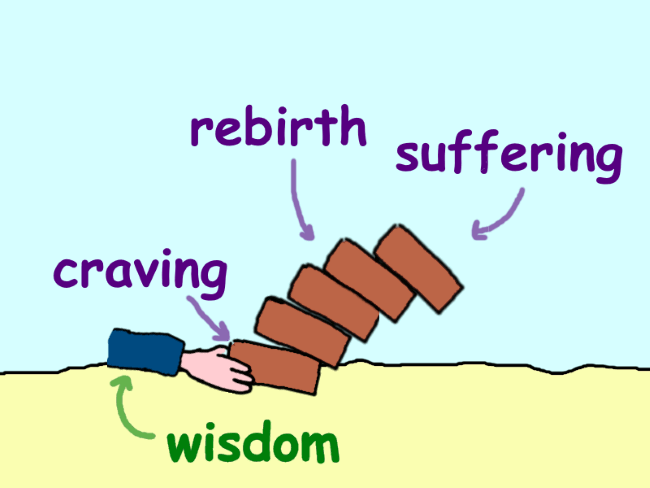

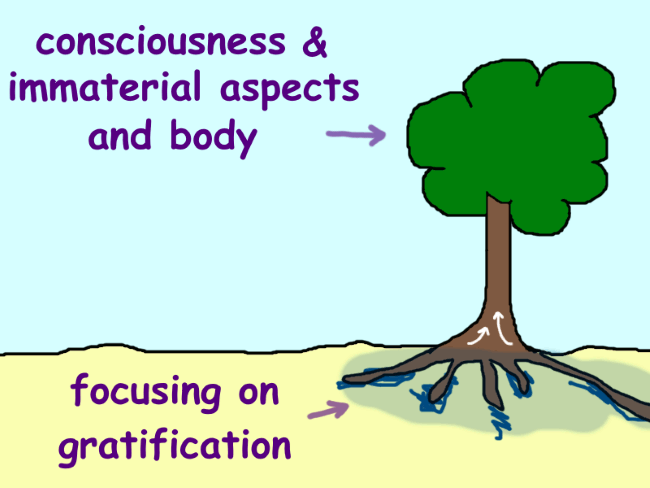

Some discourses on Dependent Arising contain only the craving sequence, omitting the preceding ignorance sequence. We already encountered an example of this at §6 and will see some others later.[61] Such explanations are possible because the craving sequence by itself already forms a complete teaching on the origin of suffering, just like Sāriputta’s short explanation of Dependent Arising in §5, and just like the standard truth on the origin of suffering itself. We can therefore also contemplate the fundamental principles of Dependent Arising by considering only the five “bricks” of the craving sequence, as in the following illustration. This can be pragmatically relevant, since the ignorance sequence contains some terms which can be hard to relate to (particularly nāmarūpa) while the craving sequence may be more readily understood.

The hand that pulls out the brick of craving I labeled ‘wisdom’ to emphasize craving cannot be removed by an act of will or by simply being mindful. It requires deep insights into the nature of life. Craving itself depends on ignorance, on not seeing reality as it is. We will always desire existence as long as we think there is some sort of real happiness to be found in it, as long as we don’t understand what suffering is. That is why the Buddha said:

§18. Mendicants, I mentioned you can find no beginning to the craving for existence, such that before that, there was no craving for existence, and after that, it came into being. However, the craving for existence is still seen to be dependent on something. I tell you the craving for existence has its nutriment, it is not without nutriment. And what is the nutriment for the craving for existence? Ignorance, you should answer.[62]

The phrase “you can find no beginning” also implies that this is about rebirth, because elsewhere it is always used with respect to saṃsāra.[63]

The following verse also depicts the dependency of craving on ignorance:

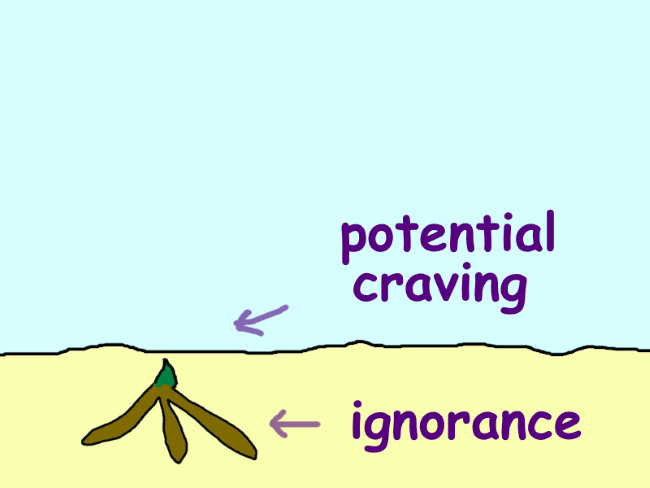

Here unknowing (aññāṇa), i.e. ignorance, is said to be the root of yearning, i.e. craving. Ignorance can be regarded as the root of craving, because craving can never be fully ended without destroying ignorance. We may be able to temporarily stop our desires, but as long as the root of ignorance still exists, the weed of craving will keep coming up.

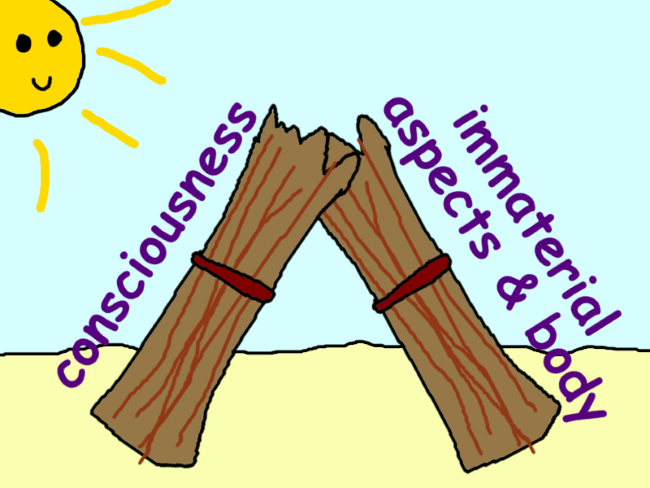

Since craving depends on ignorance, yet another way to depict Dependent Arising as a tower of bricks is with a stick between ignorance and craving, as illustrated next. It is another way to think about the two parallel sequences.

I fear this illustration may be confusing, so let me explain. As long as ignorance stays in place, there will be craving; as long as there is ignorance and craving, there will be rebirth; and as long as there is rebirth, there will be suffering. The only way to end the problem is by removing ignorance, because it is the only brick with a string to pull. If you remove ignorance, then craving will cease, and as a result rebirth and suffering will too.

Please know that the illustration is limited by nature, and also do not think of it as a causal sequence working up from the bottom. There are not two separate rebirths, for example, even though the word ‘rebirth’ is included twice. The two bricks labeled as such are in reality not different rebirth processes. In a sense we might even say they are part of the same brick. The same applies to the two bricks labeled ‘suffering’, and to ignorance and craving, which may be seen as the combined root for rebirth.

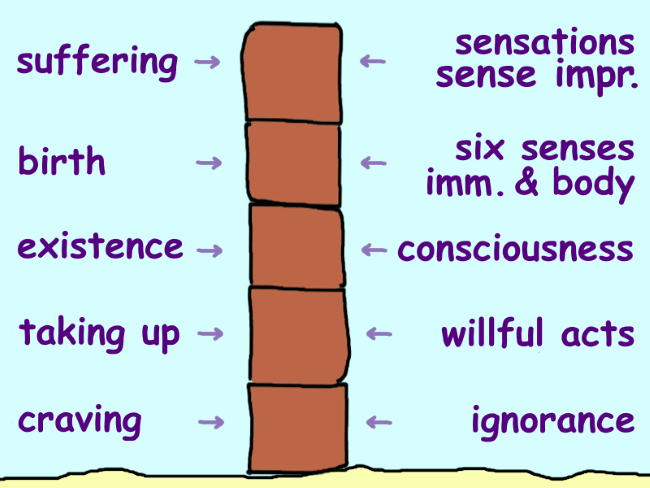

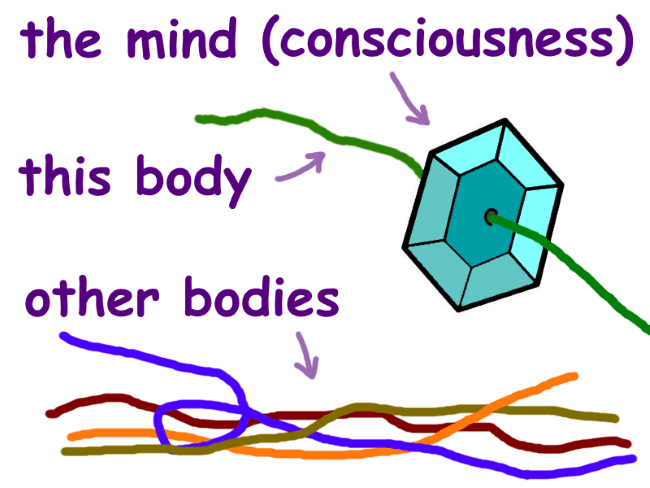

With that in mind, let me give one last tower analogy. We can also think of the twelve factors of Dependent Arising like this:

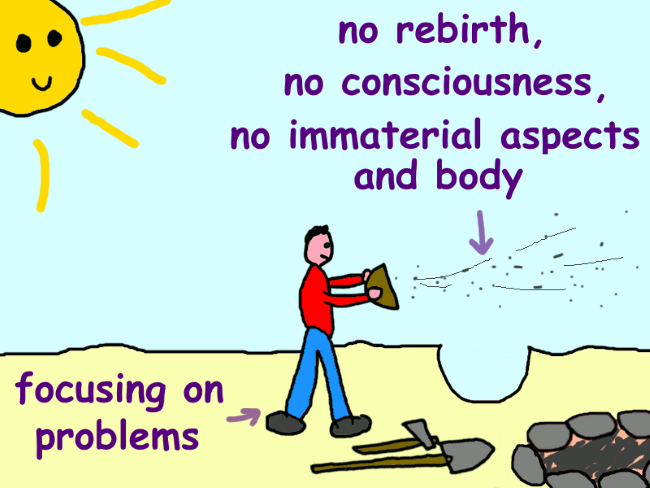

To briefly clarify, craving and ignorance are the fundamental problems. Together they underlie the more active defilements of willful actions and taking up. At death, the will causes the (re)taking up of the five aggregates, which leads to the continuation of consciousness into a next existence. This results in a birth in the respective realm, producing the immaterial aspects and body along with the six senses. Having six senses, there will be old age and death and all other suffering: all the sensations that come from sense impressions.[65] That is how the two parallel sequences function together to create suffering.

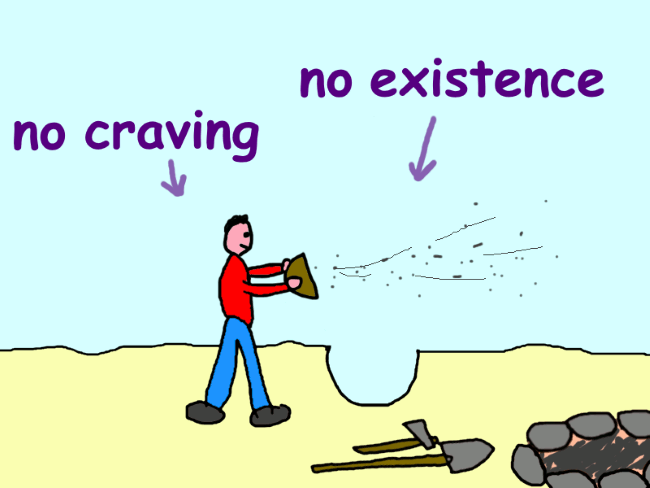

But if there is no ignorance, there will be no craving either. Lacking them, there are also no (defiled) willful actions, which include taking up. Without the propulsive power of those, there will not be another existence and no consciousness continuing after death. Then there is no next birth, and therefore also no immaterial aspects & body, and no six senses. Having no six senses, there are no sense impressions, no sensations, and therefore no suffering. And, as the Buddha would say, that is how this whole mass of suffering ceases.

The idea of there being two parallel descriptions of rebirth in the twelvefold sequence, which is also the fundamental interpretation of the Pāli commentaries, is in modern times often called the ‘three-lifetime model’. But this term is confusing and possibly ill-informed, because as explained, the factors can also span just two lives, with ignorance and craving working together in the creation of a single rebirth. To explain the general principles the commentaries give a specific example of how the factors can span three lives, but the model is not limited to this, as the commentaries themselves also make very clear. Bhikkhu Bodhi explains: “The [commentarial] distribution into three lives is only an expository device which, for the sake of concision, has to resort to abstraction and oversimplification.”[66] None of the factors are limited to one particular life either. For instance, unenlightened beings were ignorant in the past life and still are in the current one, and as a consequence they suffer in the current life and will continue to do so in the next. It does not mean that ignorance only existed in the past life and suffering only in the future one. One would think this goes without saying, but it is a perennial misunderstanding of the model.[67]

Putting this book in perspective

I hope the tower-of-bricks analogy in its various forms made the abstract idea of dependency a bit more tangible. However, it has its limits, like all analogies, and it does oversimplify some things. Most significantly, it paints a very static picture which fails to convey that rebirth is an active process. It does not properly depict the propulsive forces behind rebirth, the tendencies of the mind to move on to a next life, which are present primarily in the factors of willful actions and taking up. To offset this, Chapter 10 is dedicated to these factors. For now, with a preliminary understanding of Dependent Arising, we can turn to our main sutta, the If There is Desire Discourse, and start investigating the term appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa.

But before we do, I want to pause for one more moment to provide some perspective, because we will dive in the deep end and rarely get back to the shallows. We will discuss some of the factors in Dependent Arising that are most enigmatic, primarily those of willful actions, consciousness, and the immaterial aspects and body (nāmarūpa). It will take us into technical details, obscure texts, linguistic aspects of Pāli, and some hotly debated passages, all of which might make it seem like those who do not study a lot, have no chance of understanding Dependent Arising. But this is far from the truth. Real insights will come from meditation, not from study. The technical observations made here are not necessary to arrive at these insights.

Still, the Buddha taught Dependent Arising for good reasons. As long as we are able to appreciate some of the cultural and textual complications, there are some important lessons to be learned from every link in the chain. The following chapters will hopefully help unravel some of these complications and thereby shed some light not only on the Buddha’s teachings but also on the nature of life itself.

3. Rebirth and “name and form”

The meaning of ‘birth’, ‘old age’, and ‘death’

As explained in the previous chapter, the twelve factors of Dependent Arising should not be read in a vacuum. They have to be interpreted in a larger context, otherwise it is all too easy to misunderstand what they are about. It would be like visiting only the final lecture of a university course, when the professor summarizes all that he taught that semester, using terms that were defined in earlier lectures.

To give a concrete example, the factors of ‘birth’, ‘old age’, and ‘death’ are sometimes interpreted to refer to the constant arising and passing away of certain mind states or of a sense of self.[68] But that the Buddha did not have this in mind quickly becomes apparent once his definitions of these terms are considered. These definitions occur at least seven times in the Nikāyas, including in texts with such names as The Analysis of the Truths and The Discourse on Right View.[69] In the Nidāna Saṃyutta, the connected discourses on Dependent Arising, they occur four times:

§20. And what is old age and death? The old age of all kinds of beings in any order of beings—them being old, having broken teeth, gray hair, wrinkled skin, decreased vitality, and failing faculties: that is what’s called old age. The passing on of all kinds of beings from any order of beings—their passing away, deceasing, dying, death, demise, the end of their life, their aspects of existence breaking up, them laying down the body: that is what’s called death. The two taken together, that is what’s called old age and death.

And what is birth? The birth of all kinds of beings into whatever order of beings—them being born, their conception, their production, their aspects of existence manifesting, them obtaining the sense faculties: that is what’s called birth.[70]

It should be needless to say that states of mind don’t have broken teeth or gray hair, and are not the laying down of the body.

Another important text to consider is the Mahānidāna Sutta, the Great Discourse on the Sources [of Things],[71] which is the most detailed discourse on Dependent Arising in the Pāli Canon. It explains the connection between birth and death as follows:

§21. “Ānanda, I said old age and death depend on birth, which is to be understood as follows: If there were completely and utterly no birth at all, not of anyone anywhere—not of gods into the state of gods, not of celestials, not of spirits, not of ghosts, not of human beings, not of quadrupeds, not of birds, not of creepy-crawlies into the state of creepy-crawlies—not of any beings into any state. Then, with the total absence and cessation of birth, would old age and death occur?”

“No, sir.”[72]

Another relevant discourse is the Mahāpadāna Sutta, where the Buddha tells the story of the bodhisattva Vipassī leaving his palace in a chariot. (This story in later centuries got mistaken to be about Gotama’s own life.)[73] On his travels, Vipassī met an old person, a sick person, and a dead person. On coming back to his palace he said: “Curse this thing called birth! For old age, sickness, and death will come to those who are born.” He soon thereafter wondered, just like Gotama in §11: “People have really gotten into trouble. They are born, age, die, pass on, and are reborn again. Yet they don’t see any escape from this suffering, this old age and death and so on. When will an escape from all this finally be found?”[74] This question resulted in Vipassī’s insights into Dependent Arising, which also shows that birth, old age, and death are not states of mind or other momentary processes.

But this might have been less clear if we only considered the words themselves and not the way they are used. It’s an example of using context to determine the meaning of words. Instead of focusing on single words, we should look at the canon as a whole. Unfortunately, things are not as obvious with the factors of ‘willful actions’, ‘consciousness’, and ‘the individual’s immaterial aspects and body’, but this makes it even more important to consider as many relevant contexts as possible. Although these factors are not as clearly defined, their role in Dependent Arising is clarified in many discourses, including the one we’re primarily concerned with, the If There is Desire Discourse, which I will introduce after a note on the term bhava.

The meaning of bhava

Earlier I said my interpretation of Dependent Arising differs a little from tradition. For all intents and purposes this is only true for the factor of bhava, which I translate dependent on context as ‘existence’ or ‘state of existence’. It basically means a life in a certain place, the continuance of existence after death in a certain realm. The Pāli commentaries include in this factor both rebirth into a next existence and the karma leading to that next existence, although they do so inconsistently.[75] I do not think the inclusion of karma has any basis in the early texts and agree with Eviatar Shulman: “Bhava probably [just] means a state of existence, a rebirth as a creature in any one of the different realms. Such a reading of bhava has been suggested by numerous scholars.”[76] One of these scholars, Lambert Schmithausen, more directly stated that the interpretation of bhava as karma is alien to the early discourses and from their perspective can safely be disregarded.[77] Venerable Bodhi also notes at the Bhava Sutta: “What is meant [by bhava] is a concrete state of individual existence in one of the three realms”,[78] which are the sensual, form, and formless realms. This is in accordance with how bhava is defined in context of Dependent Arising.[79]

This interpretation also finds ancient support. The Arthaviniścaya Sūtra is a Sanskrit early text which in its section on Dependent Arising first explains the factor of bhava as occurring in three realms, just like the Pāli discourses, but then subdivides these realms further. Under the sensual realm it mentions animals, human beings, and lower gods, among others beings; under the form realm it mentions the gods of the Brahmā realm and higher; and under the formless realm it mentions the gods that spend their whole life span in one of the four formless states.[80]

The Madhyama Āgama parallel to the Mahānidāna Sutta likewise explains the link between existence (有) and birth by saying that there is existence of fish in the state of fish, birds in that of birds, and so forth.[81] The idea appears to be that the being first has to come to a certain realm before being physically born there. A curious but illuminating sutta in the Aṅguttara Nikāya confirms this when stating that certain highly developed non-returners will still obtain existence but not birth.[82] They are said to attain full extinguishment (parinibbāna) “in between”, which means in a state of existence after death but before taking a proper rebirth.[83]

Venerable Nāgārjuna, who held the same general interpretation of Dependent Arising as this book, wrote in the second century that for the liberated one there will be no further existence and that “existence (bhava) is the five khandhas”.[84] Nāgārjuna’s view is well-supported by the Pāli Canon. For example, Uttara says in the Therāgātha:

It is also said that a being after death gets reborn in a certain state of existence (bhava-upapatti).[86] The Ratana Sutta states the stream enterer won’t have an eighth bhava, meaning an eighth life.[87] At least one discourse further says that all bhava only ends at the death of an enlightened being,[88] which also disproves the common idea that it means some momentary “becoming” that ends at enlightenment.

The discourses in many other ways indicate that bhava means existence, not karma or becoming,[89] but since this difference in interpretation is not of too much concern for the current discussion on consciousness, I will leave it at this. Let us instead turn to our main discourse.

The If There is Desire Discourse

The If There is Desire Discourse is included in full here, but various sections will be requoted and clarified later, with the main purpose of explaining appatiṭṭhita viññāṇa.

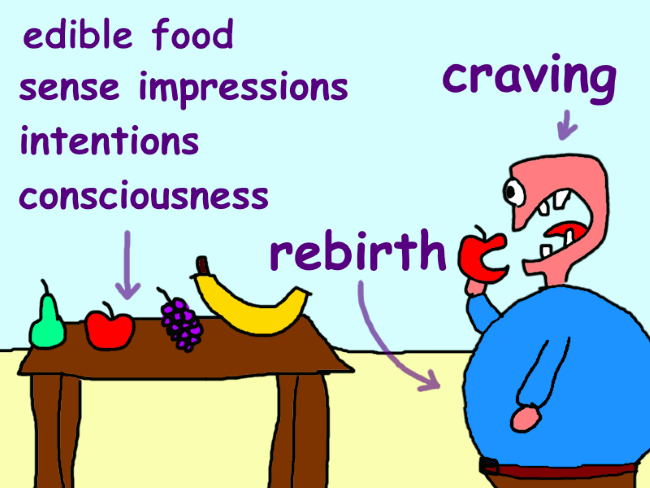

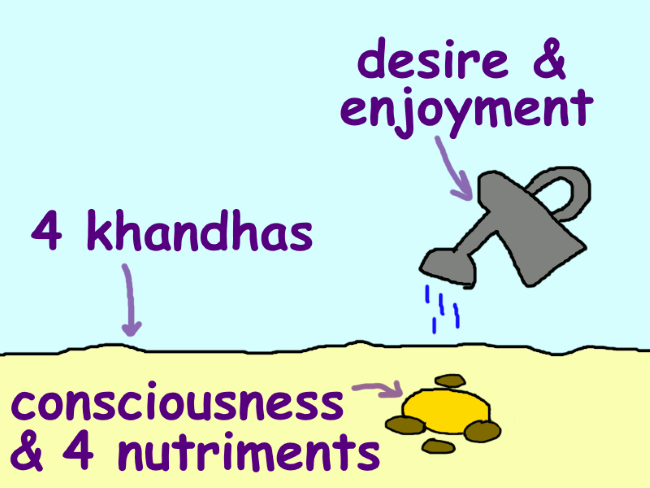

§23. “Mendicants, there are four nutriments, which maintain beings who are born and support those to be reborn. What four? The first is edible food, whether coarse or fine, the second is sense impression, the third is intention, and the fourth is consciousness. Those are the four nutriments, which maintain beings who are born and assist those to be reborn.

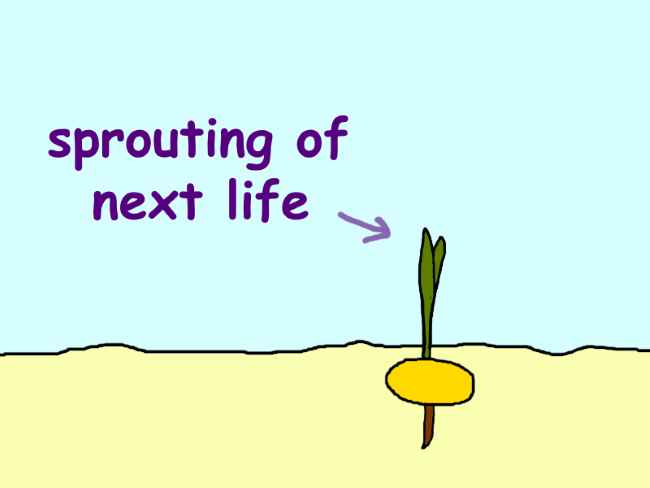

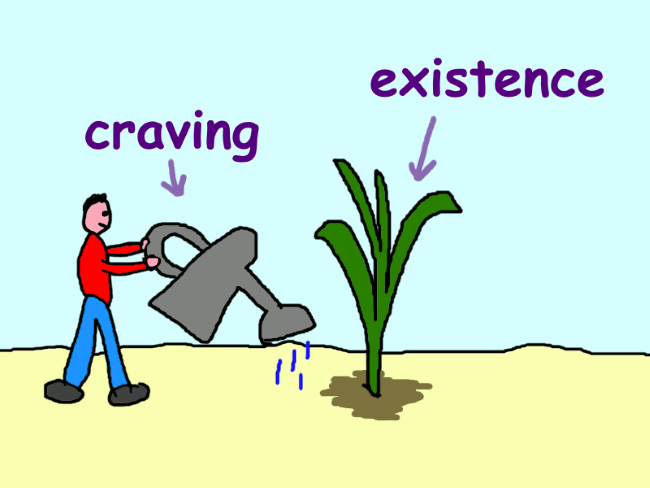

If there is desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of edible food, then consciousness will get planted and will sprout [in a next life]. Where consciousness is planted (patiṭṭhita) and sprouts, there is a conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. Where there is a conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, willful actions develop [their results]. Where willful actions develop, existence in a future life is produced. Where existence in a future life is produced, there is future birth, old age, and death. Where there is future birth, old age, and death, there will be sorrow, anxiety, and distress, I tell you.

If there is desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of sense impression … intention … consciousness, then consciousness will get planted and will sprout. […]

It’s like an artist or painter producing a complete figure of a man or woman on a well-polished board, a wall, or a canvas, using dye, lac, turmeric, indigo, and crimson. If there is desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of edible food, then consciousness will get planted and will sprout. Where consciousness is planted and sprouts, there is a conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body. Where there is a conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body, willful actions develop. Where willful actions develop, existence in a future life is produced. Where existence in a future life is produced, there is future birth, old age, and death. Where there is future birth, old age, and death, there will be sorrow, anxiety, and distress, I tell you.

If there is desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of sense impression … intention … consciousness, then consciousness will get planted and will sprout. […]

Mendicants, if there is no desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of edible food, then consciousness will not get planted (appatiṭṭhita) and will not sprout. When consciousness is not planted and does not sprout, then there will be no conception of any immaterial aspects and body. When there is no conception of any immaterial aspects and body, then no willful actions develop. When no willful actions develop, then no existence in a future life is produced. When no existence in a future life is produced, then there will be no future birth, old age, and death. When there is no future birth, old age, and death, then there will be no sorrow, anxiety, and distress, I tell you.

If there is no desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of sense impression … intention … or consciousness, then consciousness will not get planted and will not sprout. […]

Mendicants, imagine a house or a hall with windows facing the north, south, and east. When the sun rises and a beam of light enters through a window, where would that beam plant down?”

“On the western wall, sir.”

“And where would it plant down if there were no western wall?”

“On the earth, sir.”

“And where would it plant down if there were no earth?”

“On the water, sir.”

“And where would it plant down if there were no water?”

“It would not plant down anywhere, sir.”

“Likewise, if there is no desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of edible food, then consciousness will not get planted and will not sprout. When consciousness is not planted and does not sprout, then there will be no conception of any immaterial aspects and body. When there is no conception of any immaterial aspects and body, then no willful actions develop. When no willful actions develop, then no existence in a future life is produced. When no existence in a future life is produced, then there will be no future birth, old age, and death. When there is no future birth, old age, and death, then there will be no sorrow, anxiety, and distress, I tell you.

If there is no desire, enjoyment, and craving for the nutriment of sense impression … intention … or consciousness, then consciousness will not get planted and will not sprout. […]”[90]

Even though this discourse serves as an explanation of Dependent Arising, it is by no means the clearest text on the topic. It can be puzzling at first, so the remainder of this book will explain it in detail, finishing with my interpretation of the simile of the light beam.

To start, like most if not all suttas on Dependent Arising, the If There is Desire Discourse primarily concerns rebirth. That is why the Buddha said the four nutriments support those to be reborn.[91] These four nutriments also maintain beings who are already born, which is most obvious in the case of the nutriment of edible food. Stop eating, and you’ll die. This is even the case for enlightened beings. However, as its title suggests, the If There is Desire Discourse is not about eating food, but about desiring food, and this desire is what will lead to being reborn.

If at death there still is desire for the four nutriments, the discourse says, it results in rebirth. To abbreviate: “If there is desire, enjoyment, and craving […], existence in a future life is produced.” This is just a rephrasing of second truth of the noble one, which says the origin of suffering is “the craving that leads to a next life, which, along with enjoyment and desire, looks for happiness in various realms”. Notice the identical terms ‘craving’, ‘enjoyment’, and ‘desire’. Also found in both statements is the word punabbhava, which I normally translate as ‘next life’, but the expression ayatiṃ punabbhava I translate as ‘existence in a future life’. This expression is elsewhere equated to “lying in a womb in the future”.[92]

Sāriputta once rephrased the second truth as follows. Notice here the reappearance of ‘existence in a future life’ and ‘look for happiness in various realms’.

§24. Existence in a future life is produced because beings, obstructed by ignorance and chained by craving, look for happiness in various realms.[93]

To clarify the connections between these three texts, the statement by Sāriputta has the following factors:

- Ignorance and craving

- Looking for happiness in various realms

- Production of existence in a future life

The truth on the origin of suffering has:

- Craving, desire, and enjoyment

- Looking for happiness in various realms

- A next life

And the If There is Desire Discourse has:

- Craving, desire, and enjoyment

- Planting of consciousness

- Conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body

- Development of willful actions

- Production of existence in a future life

- Birth

These three texts convey the exact same ideas, just in various levels of details. Some of the terminology may be a bit elusive at first—I’m referring specifically to the planting of consciousness and the conception of the individual’s immaterial aspects and body—but in essence they all say that craving and other defilements lead to rebirth.

We can also compare the If There is Desire Discourse to the standard sequence of Dependent Arising, using the following table. Observe how certain terms reoccur in different places.

| Ignorance sequence | Craving sequence | If There is Desire Discourse |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ignorance 2. Willful actions |

8. Craving 9. Fuel/taking up |

• Craving, desire & enjoyment |

| 3. Consciousness 4. Imm. & body |

10. Existence 11. Birth |